Archive for category History

La Sombra Larga

Posted by Kevin Moloney in Digital, Film, History, Practice, Uncategorized on November 26, 2016

After the basic facts are covered the interpretation must happen – the hunt for images that not only say, ‘Fidel was here,’ but those that convey why, and what this moment means.

Cuban President Fidel Castro casts a distinctive shadow on a balcony in Santiago de Cuba during a 40th anniversary speech made from the same rail where he addressed crowds after winning the revolution in 1959.

“When Fidel dies I am dropping everything and getting on the next flight to Havana,” my friend and photojournalism colleague Phillippe Diederich proclaimed over several beers sometime around the turn of the millennium.

“¡Yo también, compay!” I slurred, punctuated with a fist pound on the bar table.

At least that’s how I remember beer- or rum-soaked conversations that repeated themselves several times over the next 5 years. We were steeped in Cuba then. The “Special Period” after the fall of the Soviet Union put much attention on what would happen in Havana and the hemisphere after El Comandante en Jefe Máximo expired. Phillippe was on and off the island, producing photo essays on its Harley riders, covering first papal visits for the New York Times and starting a novel which is set then and there.

I went four times over the next three years, the first to photograph Fidel’s speech on the 40th anniversary of his revolution. It was an incredible assignment to document a man who, with his band of barbudos, wedged a small island nation between two superpowers and had refused to leave, give up or die for decades. Fidel had been an unpredictable-turned-obdurate symbol of the Cold War.

Everything about that first trip was nostalgic for classic (or mythic) photojournalism. I was pulled aside in Cuban customs and interrogated for what seemed like an eternity about a small gift-wrapped package in my bag. “It’s a birthday gift for a colleague,” I explained. “You can open it if you like.”

“No no no. We won’t do that. So why are you here again?”

“I am here to photograph the anniversary speech in Santiago, for the New York Times.”

“Oh! The New York Times! So what’s in this box again? Who is your colleague again? Can we call her?”

“Yes. A gift. Feel free to open if it you like. It’s for the Tribune Company correspondent. Yes, you may call her. Would you like her number?”

This cycle repeated five or six times until they let me through, not accepting my offer to open the gift for them, and not calling my dear friend who was stationed in Havana. No money changed hands either. My oldest friend had come along, too, for sport and curiosity. He waited for me, puzzled, outside of customs.

On New Year’s Day, 1999, we climbed aboard a decaying Tupolev Tu-154 passenger jet flown by Cubana de Aviación. The creaking air conditioning steamed, the seat-back locks were broken in the reclined position. The toilets were locked shut, bleeding fecal aroma into the cabin. The hand-me-down Soviet plane was almost as old as Fidel’s revolution.

That night I stood among the crowd gathered in the central plaza below the same balcony where Fidel had greeted the masses 40 years earlier. El Jefe walked out fashionably late, waved, fist pounded and pontificated for several hours about el período especial and the imperialistas on the base across the bay.

Supporters cheer for Castro.

All images © Kevin Moloney, 1999

I photographed for the first 30 minutes before I had to leave to develop color film in the hotel bathroom, scan and tone color images on a grayscale laptop and upload them at only 2400 bits per second over ancient Cuban phone lines to New York. Each image took almost a half hour to transfer, and I got two images through before the late edition deadline. I was beat in all the earlier editions by wire photographers using gigantic new digital cameras that cost as much as my whole bag of Leicas.

Standing in front of the world stage has always attracted young photojournalists. The importance or attention surrounding an event like this adds weight to every decision and frame you make. I photographed in inverted-pyramid style, making nut-graph images of Fidel waving and speaking from the podium, the rapt crowd and the excitement of the event. But that can take mere moments at a scripted event where little is likely to change. After the basic facts are covered the interpretation must happen – the hunt for images that not only say, ‘Fidel was here,’ but those that convey why, and what this moment means.

That’s when I saw his shadow. By 1999 the septuagenarian insurgent was a frail old man. He was gaunt and no longer intimidating. A strong gust of wind could have accomplished what the CIA had attempted for the entire 1960s. But his shadow, stretched a bit by the angle of light, was the Fidel of the Sierra Maestra, the man who had scolded the UN and kept American influence out for decades. That was the picture. A shadow of the Cold War.

For the next week my two best friends and I wandered Havana, soaking in its cigars, rum, anachronisms and relishing in the rusty, smoke-belching ghosts of American influence. The only contemporary sign of my country was the in the ‘gringo green’ bills that changed hands on an officially blessed special-period black market.

Once, Phillippe and I waxed fantastic about what it would have been like to bushwhack our way into the Sierra Maestra in 1958, find the revolutionaries and photograph their march onto the world stage. Fidel died yesterday, just as I and colleagues Chip Litherland and Rob Mattson — my former students — and Ross Taylor traded stories of our trips to Cuba. Today is the day that I swore I would be on the next plane to Havana. But I am not, and neither is Phillippe.

Once, Phillippe and I waxed fantastic about what it would have been like to bushwhack our way into the Sierra Maestra in 1958, find the revolutionaries and photograph their march onto the world stage. Fidel died yesterday, just as I and colleagues Chip Litherland and Rob Mattson — my former students — and Ross Taylor traded stories of our trips to Cuba. Today is the day that I swore I would be on the next plane to Havana. But I am not, and neither is Phillippe.

Since those effusive conversations years ago, Fidel has passed power to his brother who already has plans in place for his own retirement. The Obama administration pried open a diplomatic door that has a rusted lock. Cuba is now just a curiosity. What Phillippe and I imagined would be a historic change event will come and go in a set of lead-story obituaries and a little bit of news analysis. Tomorrow the media’s eye will be back to a power transition that’s more timely and arguably less predictable than Fidel’s. The obdurate symbol has left the balcony.

Shooting the Mean Streets

Posted by Kevin Moloney in History, Practice, Uncategorized on March 11, 2016

School boys in the Amazon port city of Manaus leap from fishing boats into the Rio Negro below a central city market. The Rio Negro enters the Rio Solimões at Manaus to form the Brazilian Amazon. © Kevin Moloney, 1995

Henri Cartier-Bresson… Garry Winogrand… Helen Levitt… Robert Frank… André Kértész… William Klein… Jacques Henri Lartigue… Marc Riboud… Raymond Depardon… Elliot Erwitt… Joel Meyerowitz…

I started this list as I thought of who all the great street photographers might be. But I stopped early, realizing that in photojournalism (or any of its other pseudonyms) we all photograph life in the street.

Some of these photographers have made street photography the central aspect of their work, like Winogrand and Levitt. For others, like Frank and Klein, it is the piece of a complex work puzzle that made them most famous, or led to other opportunities.

It started when I was asked recently by student Danielle Alberti:

“The second you put the camera up to your eye, it seems strangers suddenly become very aware of you, and often suspicious. And because it’s in public, it’s rare that you’ll have enough time for them to relax. So we often find ourselves doing the subtle ‘lower the camera and hope autofocus works’ trick. Of course, when this trick works, I think it works well. But do you have any other street photography suggestions that might help when you want to photograph an interesting stranger without disturbing the scene (or pissing someone off)?”

This is a very common problem for young photographers (and old). We love how photographing someone pulls us into their world. But street photography can feel a bit more like an attack, or sniping. You’re often making images without explicit nor even tacit approval.

This is also the single hardest thing to which young students of photojournalism must adjust. Even those who have worked cameras for years grew up posing family or making live images of friends with whom they are comfortable. Then I come along and ask them to hunt. It’s an initially daunting task.

A bride poses for pre-nuptial photos near the Church of Nossa Senhora da Conceição, or Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, in Ouro Prêto, Brazil. © Kevin Moloney, 2009.

Many sense that the world has changed and the streets are meaner to a camera than in the past of Cartier-Bresson, Levitt and Evans. I do agree that there was perhaps a sweet spot, when cameras were familiar enough and photos not easily published in a way that the subject would feel harmed. There may be some truth in the idea that today, with the Web’s ubiquity and possibility, that any image can affect or harm you.

Maybe today, a camera can steal your soul more easily than before.

But I think this is only a partial truth. On any given street, in any time, you could find the camera-suspicious alongside the camera-nonchalant. The situation hasn’t changed that much. And official restriction on images has waxed and waned throughout photography’s two centuries.

So how did the greats act on the street?

Wait, watch, shoot. Cartier-Bresson was the cat. “Like an animal and a prey,” he said in The Decisive Moment, an educational program produced by the ICP and Scholastic in the 1970s. A nervous hunter, he scanned the world in front of him to anticipate the moment where something slight or something grand would unfold.

“That’s why it develops a great anxiety, this profession. because you’re always waiting… what’s going to happen? What what what what?

In photography you’ve got to be quick quick quick quick. Like an animal and a prey, braaam like this. You grasp it and you take it and people don’t notice that you’ve taken it.

I’m extremely impulsive. Terribly. It’s really a pain in the neck for my friends and family. I’m a bunch of nerves, but I take advantage of it in photography. I never think. I act. Quick.”

Cartier-Bresson was as subtle as he was quick, carrying one small camera and typically one small lens. He often saw a setting and waited patiently for a character or moment to complete the scene, making only a frame or two. “You shouldn’t overshoot,” he said. “It’s like overeating or overdrinking. You have to eat, you have to drink, but over is too much. Because by the time you press and arm the shutter once more, and maybe the picture was in between.”

Granted, now we have cameras that can make more than ten frames per second. How could you miss?

Travelers pass a Tyrannosaurus Rex display at Pittsburgh International Airport advertising the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. © Kevin Moloney, 2007.

You miss by becoming a massive presence on the street. The big cameras that do that can be intimidating enough. But add to that the assaulting power of a motor advance ripping at you like a machine gun, and suddenly everyone feels attacked rather than honored by the image.

Indeed we may soon find that some of the most important street images are being made with ubiquitous and inoffensive cell phones.

If Cartier-Bresson was the cat slipping elegantly and unnoticed from portico to portico on the street, Garry Winogrand was the nervous, fast-walking, bemused, gleeful, grunting American bear rumbling down the sidewalk.

His approach was as different from the French style as his images were. He waded into the stream of street traffic and deftly snatched salmon from the upstream flow.

Joel Meyerowitz described working the streets with Winogrand in Bystander: A History of Street Photography:

“Yeah. Oh yeah. You know, he set a tempo on the street so strong that it was impossible not to follow it. It was like jazz. You just had to get in the same groove. When we were out together, I wasn’t watching him — we were both watching the action around us — but I did pick up on his way of working and shooting. You could see what it was in his pictures. They were so highly charged, all you had to do was look at them and you began to assume the physical manner necessary to make pictures. They showed you right away that they were an unhesitating response.

Walking the streets with Garry gave me clues to being ready, to just making sure that I was. I had been a third baseman, so being ready came naturally. I was a quick study on that stuff, darting and twisting and the kinds of moves that were necessary to get a picture.

You know, if you hesitate, forget it. You don’t have but a fraction of a fraction of a second. So you have to learn to unleash that. It was like having a hair trigger. Sometimes walking down the street, wanting to make a picture, I would be so anticipatory, so anxious, that I would just have to fire the camera, to let fly a picture, in order to release the energy, so that I could recock it. That’s what you got from Garry. It came off him in waves — to be keyed up, eager, excited for pictures in that way.”

Winogrand was so keyed up about making photographs that he is said to have left behind 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film and 300,000 unedited images at his death in 1984.

With those numbers you might have expected him to have loved the motor drive. But he used the same little rangefinder cameras as Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank and others. He was just a relentless hunter.

A boy walks below artfully painted walls in the village of Pucará, Bolivia. Ernesto “Che” Guevara was captured by the Bolivian army in 1967 in a nearby valley and executed in nearby La Higuera days later. © Kevin Moloney, 2004.

He also moved quickly, pushing his Tri-X film to ISO 1200 and higher so he could shoot a 1,000th of a second shutter speed at f/16 and never miss a moment from blur or focus. He did this through much wider angle lenses than Cartier-Bresson. He marched down the street, straight toward his subjects and whipped up the camera the moment he or they passed. It was like a surprise punch. He wouldn’t stop, wouldn’t look and wouldn’t engage. He simply marched on with a bemused smile.

Of course, in my classes he would also be forced to engage with subjects in ways he didn’t. I require IDs and full captions to build reporting skills and skills of engagement with subjects. The game changes when you must shoot at, then talk to, a subject.

Winogrand’s work is amazing, visceral and live. But it did not need the journalist’s caption. “I don’t have anything to say in any picture. My only interest in photography is to see what something looks like as a photograph. I have no preconceptions.”

Helen Levitt, who died only last year at 95, had an eye for busy streets. Though the famously private Levitt said little about her working methods, she did tell New York Times photo critic Sarah Boxer in various interviews, “You’re talking about the past, honey. I’ve been shooting a long time.”

When asked if she followed people to photograph them, the nonagenarian said, I don’t know. Maybe. I don’t remember following anybody.”

“I go where there’s a lot of activity. Children used to be outside. Now the streets are empty. People are indoors looking at television or something.

The streets were crowded with all kinds of things going on, not just children. Everything was going on in the street in the summertime. They didn’t have air-conditioning. Everybody was out on the stoops, sitting outside, on chairs.

In the garment district there are trucks, people running out on the streets and having lunch outside.”

Cuban elementary students line up in martial form after a field trip through the city. In Cuba, the land of party-run TV, nobody stays in to watch television. © Kevin Moloney, 2001.

Was she disarming? Maria Morris Hambourg, curator of photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art tells NPR’s Melissa Block, “She’s very quiet. She’s like a cat — very slight. She moves softly. There’s no imposition of a mood or a tone or a need. If the picture didn’t present itself she would not have ever forced it.”

But Levitt did admit to Block that she used a right-angle lens from time to time, deceiving people around her about where her camera was aimed.

Perhaps Helen Levitt simply made a natural act of photographing on the street, analyzing not the act but the result.

A local theater troupe promotes an upcoming show at a Lafayette, Colo., street fair. © Kevin Moloney, 1999.

So how do you roll, then, looking for Cartier-Bresson’s complex fleeting moments, Winogrand’s sanguine street document, Frank’s dark beat poem or Levitt’s sensitive and charmed glance?

Body language is everything. We have a choice of being quick like Cartier-Bresson, elusive like Winogrand, or disarming like Levitt.

A young girl in traditional Indian dress dances through Cuzco’s Plaza de las Armas as her brother hangs onto the family dog at rear. The kids were put on display for their mother to attract alms from passers-by. © Kevin Moloney, 1996.

Carry yourself with sincerity no matter what method you might choose. If you appear to have the right to be there with a camera, passers-by will assume you do. If you relax, appear to be having fun and mean no harm, you might be more easily tolerated.

Let your intent for photographing appear on your face. If you are charmed by someone’s antics, smile as you photograph. If moral outrage shared with a subject drives you, carry yourself with concern and sincerity.

Never appear critical, unless you are as big as Garry, as surly as Weegee or as fleet as Henri.

When caught, engage. Walk up with a charmed smile and explain who you are and why you’re photographing.

Be ready to share. Offer images to your subjects and they will feel less like they’ve been exploited. Give them your e-mail address. Don’t ask for theirs.

Teens Ariel Farmer, 14, left, Kyla Sharp Butte, 14, center, and Will Sharp Butte, 15, hang out on the hood of a car in the parking lot of a convenience store to pass time on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation in southern South Dakota, Thursday, May 24, 2007. An epidemic of teen suicides and attempts has reservation adults worried. Making these images caused a worried father — even one to whom I had introduced myself — call the tribal police. © Kevin Moloney, 2007.

Expect the protective concern of parents. Children are one of the most fun of street subjects because they live their young lives with little restraint or self- consciousness. But thanks to the creeps out there, they may fear for their child’s present and future safety when someone makes a picture.

Photograph those kids just the same, if possible without affecting the scene by asking first. But as you do, glance around for parents, and if found, make eye contact as soon as possible with a nod and a smile. As soon as you can, introduce yourself and offer a business card and copies of the pictures. Proud parents will love the images and trust more the person who is unafraid to say hello.

If there are no parents apparent, ask the children where they might be and find them. If unfound, give the child a card, because Johnny or Mary will surely talk about “that nice bearded photographer with the sunglasses who took pictures of me in the park.” You’re asking for calls to the police if they don’t know who you might be.

But there is no specific recipe for success. You will surely find fun, pleasant and trustworthy people who feel honored by your attention. And even the most bright-faced young photographer with the biggest smile will encounter people accusing her of being a freak, a creep or a terrorist.

Pigeons fly overhead as a Havana resident looks up to gauge the day’s weather. © Kevin Moloney, 2001.

Get your street legs by photographing public events. People are not surprised by being photographed for no apparent reason at a parade, festival or event. Then take your confidence out to the everyday world.

Though you have a right to photograph on the street in the U.S. and most places, when you encounter resistance, apologize and walk away with a smile. You’ll never convince them of your rights anymore than they will convince you with their indignation.

Make those images. Explore the visions and moments of the street and leave a document of the 21st century as valuable as the one our predecessors left of the 20th.

…Michael Ackerman… William Albert Allard… David Alan Harvey… Werner Bischof… David “Chim” Seymour… Weegee… Edouard Boubat… Willy Ronis… Bruce Davidson… Jodi Cobb… Walker Evans… Josef Koudelka… Ben Shahn… Martine Francke… Roy DeCarava… Miguel Rio Branco… Leonard Freed… Antonin Kratochvil… Manuel Alvarez Bravo… Dorothea Lange… Marion Post Wolcott… Dan Weiner… Wayne Miller… Diane Arbus… Graciela Iturbide… Danny Lyon… Berenice Abbott… Martin Parr… Eugene Richards… Larry Towell… Alex Webb… Sylvia Plachy… Lee Friedlander…

###

Others have written at length on this subject and their work is a valuable resource. For further reading have a look at:

Bystander: A History of Street Photography, by Colin Westerbeck and Joel Meyerowitz

Thames and Hudson, London, 1994

The Photojournalist’s Canon: Part Three — From Then to Now

Posted by Kevin Moloney in Future of Journalism, History on July 22, 2011

In part 1 and part 2 I started on a list of the photographers who have made the greatest influence on successive generations of photojournalists. To recap, this is a start on a “canon” to which you may contribute a suggestion. I’m looking not just for a list of the “great photographers” nor the most famous or successful. I’m looking for photographers who:

- Produced documentary work reflecting the important standards and ethics of the profession,

- Stood the test of time by repeatedly producing notable work, and

- Innovated in the art or profession by being first to adopt an important style or approach, break a barrier or rise above the limits of the day.

Think of who might have been the first to think of something or do something important. That’s a tougher standard than might be immediately apparent.

So let’s wrap this up with a ‘cambrian explosion’ of styles, where the photo essay was codified, scrapped and rearranged in a score of different ways, the portrait took on a whole new meaning(s) and what we reveal of subjects is less rigid. This is a period where photojournalists take the mandate of documenting the world and interpret it personally. This is the toughest list to assemble because the farther you look back, the easier it is to spot the innovators and revolutionaries. Sometimes it takes the length of a career to see what changes or new ideas a photographer brought to the profession. I’ll be conservative in naming people or groups here, but that doesn’t mean you can’t chime in. Drop a name or two in comments, with a few sentences about what he, she or they did to change the face of photojournalism.

Simply add boiling water. © Estate of Arthur “Weegee” Felig.

Weegee — If being a newspaper or wire photographer was “feeding the machine” as has often been said, Usher (Arthur) Fellig fed it the morsels with the most gristle. As a freelance New York crime photographer in the 1930s and 40s, Fellig earned the nickname “Weegee” for his uncanny ability to beat the cops to a shooting. They assume he had his fingers on a Ouija Board to get there. In reality, he had a police radio in his car with a darkroom in the trunk, lived in the center of the crime in Hell’s Kitchen, and ran on the motivation of a paycheck. He was one of hundreds of Speed-Graphic-wielding freelancers plying the same trade, but Weegee had a rare sense of humor and irony in his images of New York’s underbelly, and Barnum’s penchant for self promotion. He was the star of a particular way of working that still includes many hot-spot-hopping freelancers and wire contributors. But he is the one that got the MOMA and ICP exhibitions, and yes, he would have pointed that out to you.

Magnum Photos — Magnum Photos is not the first photojournalism agency, nor the first group of photographers to coalesce. Magnum changed the idea of the ownership of images, insisting that the copyright of the work remained the photographer’s property. The prominence of the photographers who founded it — Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, David “Chim” Seymour and George Rodger — gave the cooperative and its subsequent members the leverage to change business practices in the profession of photography for the better. It remains the preeminent photojournalism agency, and the style of its members has influenced every subsequent generation of photographers and photojournalists.

Wake, Deleitosa, Spain, 1951. © Estate of W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith — Smith had the news sense of Alfred Eisenstaedt, the understanding of combat of Capa and the technical polish of Walker Evans. He is also our model of obsessive-compulsive, irascible and addicted artist of the real. But his greatest contribution was in the redefinition of the photographic essay. In 1949 he broke with LIFE’s script for a photo essay on a country doctor in Colorado to photograph what he saw (and a little of what he wished to see). That essay and subsequent ones on Dr. Albert Schweitzer and nurse-midwife Maude Callen reshaped the way we approach the long form of photojournalism. An essay on a Spanish Village under fascist rule is arguably the template National Geographic has followed since for covering a place. His last essay on mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan, is one of the most powerful and complete reportages on the environment ever published. And his failed essay on Pittsburgh at mid century is one of the most beautiful, compelling and epic failures of the profession. He was also a compulsive audio collector, amassing thousands of hours of documentary sound from a New York City loft from the late 1950s to the early 1970s. His personality was a cautionary tale for how to act and how not to act, but his essay work will echo for the foreseeable future.

Elevator operator, Miami Beach, 1955. © Robert Frank

Robert Frank — While Smith was crafting the public, mainstream photographic essay for LIFE and Magnum Photos, Frank was creating a model of the personal photographic essay. On a Guggenheim grant in 1955, Frank crossed the U.S. photographing the world’s foremost power with the eyes of a foreigner. The Americans was an overtly critical look in the mirror for most Americans and flew directly in the face of Steichen’s contemporaneous Family of Man. Walker Evans was one of the few who saw the value in the images. “It is a far cry from all the woolly, successful ‘photo-sentiments’ about human familyhood,” he wrote. Where Smith’s stories may assemble virtual bullet points in the images chosen, Frank’s are personal, subtle and tease the emotions of the reader. Smith’s images were about the emotions of the subject. Frank’s work has influenced the craft as deeply as Smith’s and his approach has emerged in the work of others from Larry Fink to Danny Lyon, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Bruce Davidson and probably you. He is an artist, poet and filmmaker, and says he lost his Leica in 1962 and didn’t mind.

New York, 1954. © William Klein

William Klein — If Frank’s work was about the distance and ennui of American society, Klein’s poked your nose and boldly stated that New York is Good and Good For You. His 1956 book by that name grabbed you by the shirt and dragged you into the streets of the city at close range, with very wide-angle lenses in a way that wouldn’t let you escape. Klein took that energy into the fashion world where he and a few others created the look of fashion images in the 1960s.

© Elliott Erwitt

Elliot Erwitt — I once sat at JFK with a fresh copy of Erwitt’s Personal Exposures catching the annoyed glances of fellow air travelers because I could not contain the out-loud laughs as I paged through the book. As a journalist Erwitt is incisive, catching one of the iconic moments of the Cold War among others. But he is most notable for an irrepressible humor in his images that has never — to my knowledge at least — been matched by anyone. His work is a stream of dry and witty jokes, slapstick humor and uncanny timing.

Jaqueline Kennedy Onasis. © Ron Galella

Ron Galella — In class I often ask new students if they would consider the paparazzi to be journalists. There is no genre of documentary photography more maligned than those who chase celebrity the way Weegee chased murders, and the students’ responses reflect that viscerally. But if the moment be real, I argue, what’s the difference? The idea of doing it still makes my skin crawl, but I have to admit that it is the journalism of the low-brow we all crave from time to time. The granddaddy of these used-car-salesmen of the profession is Ron Galella, the paparazzo who would not let Jackie O out of his sight, resulting in lengthy legal battles. In one case he was given a requirement to stay 150 feet away from his favorite subject. The second required him to stop photographing her for life. Marlon Brando punched him in Chinatown. Sure, there were celebrity-following camera jockeys long before him and will be as long as there are celebrities. But Galella took dauntless obsession and anything-for-the-shot to new heights (or should that be depths?).

© Josef Koudelka

Josef Koudelka — There are a few regions where reality and magic blend in the eyes of artists and the words of poets. Latin America and Eastern Europe have both produced remarkable photographers whose work reflects the magic realism of Borges, Márquez or Llosa. If I knew eastern European authors I would include a few of them in simile too. His images of the rituals and lives of Slovakian gypsies are infused with the magic we imagine in their lives. They are intimate images the way Frank’s are, but the emotions come not just from the photographer but seemingly from the subjects themselves. And his work on the Soviet invasion of Prague in 1968 demonstrates a bravery fictionalized by Milan Kundera in The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

Refugees in the Korem Camp, Ethiopia, 1984. © Sebastião Salgado and Amazonas Images

Sebastião Salgado — He began his professional life as an economist for the International Coffee Organization but soon drifted to photography through which he has documented the social and political circumstances of the people most directly affected by the production of that and other commodities. This is firmly in the traditions of Riis, Hine and the FSA among others. But what makes Salgado’s work different is a fusion of the magic realism of Álvarez Bravo or Koudelka combined with the compositional complexity of Cartier-Bresson, and a skill for revealing the dignity in his subjects, no matter their circumstances.

Street kids, Seattle. © Mary Ellen Mark.

Mary Ellen Mark — Many photographers have relished photographing subjects at whom you might like to stare — Richard Avedon’s In the American West, Diana Arbus’ work — but Mark developed early a style that blends social documentary with the made-you-look quality of subjects on the fringes of society. You may sometimes be shocked, but you never want to turn away from her empathetic stories.

Alexander Calder © Arnold NEwman

Arnold Newman — Until the latter half of the 20th century, the posed, formal portrait was as much about vanity as it was a document. Portraits reflected the Old Masters in style and composition more than they really illustrated the life or personality of a subject. Perhaps the greatest practitioner of the environmental portrait was Arnold Newman, who could coax personality from a subject and reveal it in a telling environment better than anyone. There have been portraitists who have lit better, composed better, been more stylized and flashy, but few have taught us so much about the subjects themselves.

Birmingham, Ala., 1963. © Estate of Charles Moore.

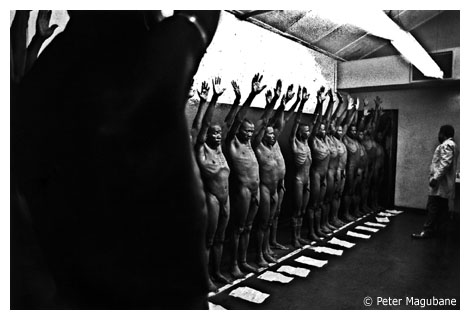

Mine worker inspection, South Africa. © Peter Magubane

Charles Moore and Peter Magubane — Few Western photojournalists ever find themselves covering strife and revolution in their own backyards. Both of these men — Moore in the American South during the Civil Rights Movement and Magubane in South Africa under Apartheid — photographed their own cultures, neighbors and backyards in upheaval. It is always more difficult to photograph one’s own world than it is to photograph the foreign. These men, and others like them such the “Bang Bang Club,” Micha Bar-Am and others in similar circumstances have had to turn the cameras onto their friends, neighbors and families to tell the story of a revolution, and in the process created documents that explain deeply from within the story itself.

© Estate of Ernst Haas

Cuba. © Alex Webb

Ernst Haas and Alex Webb — Color photography has existed since the beginning of the 20th Century, but it did not reach maturity until color print reproduction was common and affordable in magazines. Until Haas and Webb, color was a secondary element in a photograph — more detail, more reality but less so an element of design. However Haas made color a principle element of mood and emotion, and Webb uses it as a structural element of composition. For both, color was as primary a reason to make an image as the moment in the scene, the social or historical significance or other graphic elements of the photo. They see color better than their predecessors.

Arnold Schwarzenegger. © Annie Leibovitz

Annie Leibovitz — Whereas Newman was out to find and photograph the person behind the celebrity, Leibovitz developed a style in the 1980s of photographing the celebrity in front of the person. Her subjects reveal not their innermost selves, but the crafted stage persona they have all developed and that is the source of their fame. And like many styles and approaches, Leibovitz has been emulated with failure more often than success as many photographers strive for stylization over substance in portraits. In addition to the portraiture, Leibovitz also revolutionized the way we document celebrity behind the scenes with her complete access following the Rolling Stones in the early 1970s.

And who comes next? I see trends away from the crisp realism of the last century toward an edgy, blurred point of view that feels like the pictorialists taking on the subject matter of Lewis Hine or Robert Frank. Who is the progenitor of that mood or another possible shift in how we approach our craft or profession? I am just one opinion with one knowledge set. You tell me who comes next.

Please note, most images on this post are linked directly from the originating sites rather than downloaded and republished. Please forgive any dead links.

The Photojournalist’s Canon: Part Two — Early 20th Century

Posted by Kevin Moloney in History, Uncategorized on July 18, 2011

In the last post I started on a list of the photographers who have made the greatest influence on successive generations of photojournalists. To recap, this is a start on a “canon” to which you may contribute a suggestion. I’m looking not just for a list of the “great photographers” nor the most famous or successful. I’m looking for photographers who:

- Produced documentary work reflecting the important standards and ethics of the profession,

- Stood the test of time by repeatedly producing notable work, and

- Innovated in the art or profession by being first to adopt an important style or approach, break a barrier or rise above the limits of the day.

Think of who might have been the first to think of something or do something important. That’s a tougher standard that might be immediately apparent.

So here’s part two, the photographers that opened the 20th century. This is the generation of photographers who picked up the new small cameras that shot roll film and started documenting life in action. They created what we consider photojournalism out of a near vacuum:

Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Grand Prix de l’AAF, 1912 © Estate of Jacques Henri Lartigue

Jacques Henri Lartigue — Lartigue picked up a camera as a very young boy and aimed it at his adventurous family at the end of France’s Belle Epoque. His best-remembered images are of auto races, early airplanes and cousins leaping in midair. His early images are of the fascinations of a young wealthy boy of the gilded age, but they show a joyful innocence unmatched in most documentary work. They are exuberant, ecstatic and defy the limitations of the photography of a century ago, capturing peak action and decisive moments with very slow plate cameras. To any child — which is what he was when he made his best-remembered images — there are limitless possibilities and no hard rules. His work shows the possibility in working without any adult-world-imposed constraint. He lived a long life, working as an illustrator and painter, then again as a photographer after his rediscovery by John Szarkowski and the Museum of Modern Art in the 1960s.

‘The Terminal’ or ‘The Car Horses’ New York 1893 – By Alfred Stieglitz © Estate of Alfred Stieglitz

Alfred Stieglitz — Photojournalism is inextricably attached to the art of photography, as we make thorough use of light, form and composition in our work to change the world. No single photographer or curator did more to battle for the status in America of photography as an art or to promote its practitioners. His own work is often documentary, capturing steaming horses on cold New York mornings, and street life on the edge of night much as his European contemporaries Eugène Atget and Brassaï did in Paris. He promoted many photographers on or linked to this list, from Paul Strand and Edward Steichen to Ansel Adams who, in addition to his famous landscapes, documented the Japanese internment camps of WWII. Though his photography career crosses the 19th and 20th centuries, his influence was strongest in the years between the world wars.

Preparing for the strike on Kwajelein Photo by Edward J. Steichen aboard the U.S.S. Lexington (CV-16), November 1943

Edward Steichen — Few working lives spanned more interesting changes in photography, more genre of the art and more positions of influence than those of Edward Steichen. He began his career at the dawn of the 20th century by making an amazing array of portraits of the luminaries of the day, from J.P. Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt to Pierre August Rodin, Henri Matisse and George Bernard Shaw. His portrait style has resonated through subsequent generations from Yousuf Karsh and Philippe Halsman onward. That work moved him quickly into the world of fashion where his images helped define the styles of magazines like Vogue for a generation. Himself a WWI Signal Corps aerial photo veteran, Steichen volunteered for duty in WWII, was commissioned by the navy at the rank of commander, and formed a team of photographers to document the war in the Pacific. His team included notables Wayne Miller, Charles Kerlee, Fenno Jacobs and Horace Bristol, among others. His own images, made of combat when he was already in his 60s, are notable for their capture of war action and the strange, graphic beauty of naval aircraft carriers. On war’s end, Steichen took the position as the first-ever curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York he mounted the “Family of Man” exhibition in 1955 which gathered images from around the Cold-War-stricken world to illustrate his point that, “The mission of photography is to explain man to man and each man to himself. And that is no mean function.” The massively successful exhibition helped define what photojournalism was at midcentury and influenced most of the work that has come since. Inclusion in the exhibition launched the careers of many photojournalists around the world, and the exhibition catalog has remained in print for more than 50 years.

Shadows of the Eiffel Tower, Paris, 1929, by André Kertész © Estate of André Kertész/Higher Pictures

André Kertész — Cartier-Bresson once said on behalf of himself and others of his generation, “Whatever we have done, Kertész did first.” Kertész started photographing in Hungary before WWI, and through his service in the Hungarian army in that war. After developing his style — one of intricate and graphic compositions, geometric patterns and decisive moments — he moved to Paris in 1925. His work there was warmly received, but in 1936 he accepted an offer to go to New York, both to work and escape the Nazi threat building in Europe. He stayed until just before his death in 1985. He was also an early adopter of small handheld cameras allowing him to catch fleeting moments and travel lightly. Kertész’ work is artful, perfectly crafted, subtle, delicate and deeply inspiring. In perusing it you can see not only his brilliant seeing, but premonitions of all that followed.

Wall Street, New York, 1915. © Estate of Paul Strand

Paul Strand — Strand was not a self-described photojournalist and he is certainly better known as an art photographer. However he was instrumental in breaking the photography of the early 20th century away from the soft-focus romantic “pictorialism” of the day and showing that the power of the medium is crisp realism. He made powerful documentary portraits and photographic essays, and his art remained rooted firmly in the real world. And in anticipation of the early 21st century and visual journalists like Tim Hetherington, he was an accomplished cinematographer and film maker, documenting New York, the Spanish Civil War and the struggles of Mexican fishermen in his cinema career.

Aristide Briand, pointing at Erich Salomon, exclaims, “Ah, there he is, the king of the indiscreet!” Paris, Quai d’Orsay, August 1931. © Estate of Erich Salomon.

Erich Salomon — Advances in photojournalism come on the heels of technological advancement. From images of the still and quiet death on mid-19th-century battlefields to the galloping horses of Muybridge, film speed, camera handling and lens speed have all influenced the state of the visual art. But until the 1920s, candid, handheld photography with a small camera was a challenge. Though “press cameras” and SLRs had been around for decades, the first camera that actually allowed the kind of photography we now relish was the Ermanox. It was a 645-format plate camera with a focal plane shutter that could shoot up to 1/1000 second (also not new), but it had an incredibly fast f/1.8 lens. On that format it was as difficult to engineer and had less depth of field than a 50mm f/1.0 has in the 35mm era. Complicating its use was that the focus at that narrow depth of field was done simply by guessing the distance. The master of Ermanox use was Erich Salomon, a German Jewish law school graduate who introduced himself as “Doctor.” With little prior photo experience, Salomon picked up this new little camera (one nearly universally shunned by professionals) and started talking his way into venues where no one had yet ventured with a camera — courtrooms, political meetings, the homes of the famous. He always dressed impeccably, conducted himself with the manners of a person who might be expected to be at such scenes and made pictures either overtly or by concealing the camera. Soon his images were being published by Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung — a political weekly that had pioneered visual reporting. Salomon was fluent in several languages and a talented political observer. Politicians either loved him and invited him into their worlds, or hated him and worked to make sure he was spotted at scenes. He also pioneered the technique of handing over unexposed film with supplicating apologies when caught where he should not be, and keeping the exposed films for publication. Though he had considered emigrating to the U.S. where his images were also being used by the new illustrated weeklies, he kept putting it off until in 1943 he and his family were forced into hiding. They were betrayed by a meter reader who noticed the heavy gas consumption at the house where they were staying in Holland. Salomon was killed at Auschwitz in July 1944.

A goalkeeper dives for the save, Budapest, 1928. © Estate of Martin Mukácsi.

Martin Munkácsi — Munkácsi is perhaps most famous for making the image that inspired Henri Cartier-Bresson to drop a paint brush and pick up a camera. The image — of a trio of boys running into the surf of Lake Tanganyika — is his most often reproduced, thanks to HC-B. But behind that image is a career as an action photographer. In Europe before WWII he was the toast of the fashion and sports photography world. Anyone who assumes sports photography is only possible with autofocus and ten frames per second needs to look at his tightly cropped, shallow-depth, razor-sharp images of goalies diving for a save or polo riders in mid-strike made in the 1920s on 4X5 and larger plates. Skiers breaking over cornice lines, dancers in flight, and models in mid leap hallmark his work. He went to challenging lengths to get his images — laying in the surf with a bellows-focused camera to photograph swimsuit fashion in the 1930s. Like his Hungarian compatriots Andre Kertész and Robert Capa, he was drawn to the U.S. before the war, and like Kertész, he languished here among much less inventive editors and publishers.

Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, 1933. © Time-LIFE, Inc.

Alfred Eisenstaedt — Eisenstaedt’s career began in Germany in the late 1920s with the illustrated press that arose there and ran into the 1990s for LIFE magazine, for which he was one of the first staff photographers in 1936. His last photographs were of Bill Clinton and family in 1993. He used small cameras from the start, making active images in low light on the heels of Erich Salomon. A few of his images are enduringly remarkable — Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels glaring with hatred, The V-J Day kiss in Times Square, a parade of gleeful children marching behind a drum major. But by today’s standards most of his images — though technically solid and timed well — seem boilerplate. We feel we’ve seen them so many times before. But what must be remembered in looking at his vast body of work documenting most of a turbulent century, is that Eisenstaedt didn’t have Eisenstaedt to emulate. He is the template for most of what we do. His journalistic sense was impeccable. Not only did he define the genre of photojournalism in how he worked, but he defined what it looks like to be a professional photojournalist. There is some Eisie in everything we do.

Bullring, Valencia, 1933. © Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson — He said that Kertész did it first and that Munkácsi influenced him. Can we put him on this list? I will argue yes, and not because he’s my hero of heroes. HC-B’s influence on all photojournalism since the 1940s is so wide and so deep it would be remiss to consider him derivative. His innovation comes from taking Kertész’ form and grace and combining it with Munkácsi’s timing to define that decisive-moment photojournalism and street photography we so love. He produced, directed and filmed documentary films during the Spanish Civil War and again in the U.S. in the 1970s. He fused high art and incisive journalism more directly than anyone before, and cofounded one of history’s most influential cooperatives to promote it.

Running for shelter during the air raids. Bilbao, Spain, 1937. © Estate of Robert Capa and Magnum Photos.

Robert Capa — As seen in the last post, war photography was not new and the bon-vivant photojournalist persona was not either. But Capa amplified both to as-yet-unseen levels. Capa was a talented self-promoter, inventing a name with his collaborator Gerda Taro (also an invented name) to make his work seem more valuable to editors. He photographed and filmed conflicts from the Spanish Civil War to the Japanese invasion of China, WWII, and Indochina where he was killed in 1954. His gritty few frames of the Normandy landings on D-Day are some of the most iconic images of the biggest conflict in world history. His style and approach have influenced all war photography that has followed, from David Douglas Duncan to Larry Burrows, Don McCullin, James Nachtwey and the late Chris Hondros. His high-stakes, high-living style has become the cliched image of the gambling, loving, champagne-drinking world photojournalist, so much so that Hitchcock fictionalized him in Rear Window. And on founding Magnum with Cartier-Bresson, David “Chim” Seymour and George Rodger, he was instrumental in reclaiming rights to their images for photographers.

Walker Evans, ‘Truck and Sign’ (1928-30).

Walker Evans — We know Walker Evans mostly through his work for the Farm Security Administration Photography Program where he produced some of his most meaningful images. But Evans was an accomplished documentary photographer before he joined Roy Stryker’s team. More interestingly, he was fired from the FSA. Evans and his work are as straight as an arrow. He took the idea of documenting seriously, using large format cameras to meticulously correct perspective and distortion on images of simple buildings throughout Depression-era America and in Cuba. But his images are far from artless. They prove over and again that art does not need to come from gimmick or visual trickery, and that the subtlety of light, shape and content can send a powerful message about the state of a culture. SX-70 Polaroids he made in the 1960s presage even a current fascination with those films and their phone-app emulators.

Relief line following the Louisville Flood, 1937. © Estate of Margaret Bourke-White and Time-LIFE Inc.

Margaret Bourke-White — Bourke-White was not the first woman photographer, but she broke more glass ceilings and social barriers than any other. She was hired as a staff photographer for Fortune on the cusp of the Great Depression in 1929, was the first Western photographer allowed to photograph Soviet industry in 1930, and a staff photographer and author of the first cover of LIFE magazine in 1936. Like her contemporary, Dorothea Lange, she photographed the dire conditions of the Great Depression, and authored a book (with then-husband Erskine Caldwell), Have You Seen Their Faces. She was the first authorized woman combat correspondent of WWII. Her images of the Nazi death camp at Buchenwald are some of the principle historical evidence of Nazi atrocities. With Cartier-Bresson she photographed the partition of India and Pakistan and the violence it spawned, and made moving portraits of Mohandas K. Gandhi on the eve of his assassination. Her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, is a valuable read for any photographer.

Ingrid Bergman at Stromboli, 1949. © Estate of Gordon Parks.

Gordon Parks — Parks was a classic Renaissance man: A concert pianist, composer, photographer, writer, and filmmaker. There were black photographers before him, but none who elbowed his or her way through the discrimination of the day as effectively as him. He was born in Kansas and began his adult life as a railroad porter, but as a very young man he picked up a camera to photograph the plight of migrant workers. He progressed from that first roll to photographing fashion in St. Paul, which caught the eye of Joe Louis’ wife Marva. From there he branched to portraits of black society women in Chicago and on to documentary work about Chicago’s South Side in the Depression. An exhibition of that work caught the eye of Roy Stryker who gave him a fellowship with the FSA. His first images there struck right at the heart of how the nation’s Capitol treated its black workers. After the FSA disbanded, Parks moved to Harlem where he worked for Vogue and then LIFE where he was the first black journalist. He photographed Malcom X, Stokely Carmichael, Muhammad Ali and produced a book-length essay on an orphan in a Brazilian slum. But that was just his photography career. He was also a successful novelist and poet, and wrote and directed the 1971 “blaxploitation” hit movie Shaft, for which he also wrote the score and popular theme.

Striking Worker, Assasinated. 1934. © Estate of Manuel Álvarez Bravo

Manuel Álvarez Bravo — Like others on this list, he described himself as a photographer, not a photojournalist. And like others he was a surrealist above all in the early 20th century. But his often political work brought attention to the struggles of a nation. His portraits, art and surrealism inspired generations of photographers from Tina Modotti to Graciela Iturbide, Flor Garduño, Miguel Rio Branco and Cristina García Rodero. He was the first Latino photographer to rise to prominence, and he helped define the style of a hemisphere.

Homeless, Atoka County, Okla., 1938, by Dorothea Lange

The Farm Security Administration Photography Program — Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, Gordon Parks, Jack Delano, Russell Lee, Carl Mydans, John Vachon and Marion Post Wolcott. It was the dream team of documentary photography, assembled by economist Roy Stryker to photograph the plight of the American farmer during the Great Depression. The purpose was propaganda, really. But neither Stryker nor his photographers felt they needed to create advertising. The truth of the American economic situation spoke for itself, and as a result we have an incredible document of America at one of its most difficult points. Many of the photographs are the icons of that age, burned into the retinas of Americans born more than a half century after they were made. Most of the photographers went on to long photojournalism careers for LIFE, Look and other popular magazines. Mydans, who with his reporter wife spent time in a Japanese prison camp after the fall of the Philippines, made one of the iconic images of the Pacific War. Stryker carefully populated his staff to allow access to both genders and as many races as possible, to leave no group undocumented. Their work forms a template for cooperative documentary projects and expands on the social documentary started by Riis a half-century earlier. With every subsequent economic crisis, their work has been republished and emulated.

Please note, all images on this post are linked directly from the originating sites rather than downloaded and republished. Please forgive any dead links.

The Photojournalist’s Canon: Part One — The First 50 Years

Posted by Kevin Moloney in Future of Journalism, History on July 14, 2011

This is a set of posts about inspirations and influences. I know you may have landed here following a search about camera equipment, but to quote Peter Adams, “A camera didn’t make a great picture anymore than a typewriter wrote a great novel.” Photography is about seeing and making any camera of any sort work for you. This post should cite many examples of that.

A “canon,” as used here, is a list. It may be a collection of rules from a religious authority or a list of the great books, music and art of history. This canon is a rough start on a list of the most influential photojournalists or documentary photographers (largely the same thing) to have aimed their lenses at the real world.

The idea came to me as I was looking for a favorite recipe the other day (poblanos en nogada if you’re curious). I went to the stack of cookbooks and pulled Raymond Sokolov’s The Cook’s Canon: 101 Classic Recipes Everyone Should Know, and found myself wondering who or what would be on a photojournalist’s canon.

This could be approached a few different ways: It could be a list of great works, a list of great essays, a list of great photographers. I chose the last because great works or great essays can be isolated incidents in a career, or can be forgotten or never escape a small readership. Great photojournalists have succeeded in not only repeatedly producing great work, but in getting it seen by masses and collected by institutions.

Why bother? Everyone’s list may be different. Some will argue the merits of who makes such a list. Who am I to decide? But that’s the beauty of a blog. This is ostensibly a conversation, and I make no pretense that I have the final word. Please feel free to add to this list in the comments with a name and a few sentences to make your case.

And what do you care? For many, this should be a reminder of who influenced us to take up the profession whether they are on this list or not. For students of the art/craft/profession, it is a list of those worthy of some study. For all it will hopefully be inspiration to truly innovate in what we do.

In order to have a pattern and avoid excessive repetition of styles, here are the standards I have selected. He or she (or maybe they) should have:

- Produced documentary work reflecting the important standards and ethics of the profession,

- Stood the test of time by repeatedly producing notable work, and

- Innovated in the art or profession by being first to adopt an important style or approach, break a barrier or rise above the limits of the day.

This isn’t as easy as it might seem to be. For example, take Henri Cartier-Bresson. Of the decisive-moment-layered-geometric-composition style is he the first? Or did André Kertész do all that first? Should Marc Riboud, also one of my personal heroes, be included? Or does his work stand firmly in the same genre as HC-B? The nuances and potential arguments are many. But what the hell. It’s worth a try. If you add to the list, make a point about why they were first or best at an approach. If I were just making a list of favorites, this would be a different sort of list.

In order to make this an approachable read, I’ll start with the first 50 (or so) years:

Roger Fenton — This guy may have been the first photographer to drag a camera into a war zone. He photographed the scene of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” in the Crimea in 1855. Though until the 20th century photography was seen not as art but as document, Fenton may have been the first photojournalist. Granted, his ethics would certainly not pass even 20th-century standards, but he made a few long exposures on sluggish glass plates that for the first time transported viewers to the scene of a major world event.

Roger Fenton — This guy may have been the first photographer to drag a camera into a war zone. He photographed the scene of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” in the Crimea in 1855. Though until the 20th century photography was seen not as art but as document, Fenton may have been the first photojournalist. Granted, his ethics would certainly not pass even 20th-century standards, but he made a few long exposures on sluggish glass plates that for the first time transported viewers to the scene of a major world event.

Bodies of Confederate dead gathered for burial after the Battle of Antietam, September 1862, by Brady photographer Alexander Gardner.

Mathew Brady — Six years later this star American photographer arranged a similar thing. Brady was a studio photographer noted mostly for his portraits, including those of Abe Lincoln made — as many assume — by securing the president’s head to a metal rod so he could hold still for the long exposure. Imagine… “Excuse me, Mr. President while I strap your head in place…” But Brady packed up his studio onto a wagon and sent assistants out to the scenes of death and mayhem in the American Civil War, where they photographed aftermath mostly, because dead soldiers didn’t move. They did, however, make images of men posed in bivouacs and other situations where they could hold still for the daguerreotype plates. His crew, which included notables Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan, and other period photographers also produced work in 3D for stereoscope viewers. Today we worry about shocking and desensitizing our readers, but back then they delivered the gore in 3D by selling cards in stores. To end this lengthy note, we might say Brady was as much the first photo agent as he was an early photojournalist, running a team of photographers to cover the war. Like Fenton and others of his era, the manipulations of all their images before and after the exposure are legendary. But as I’ve noted here before, ethics evolve. He should be on this list for his innovations. And in an end far too common on this list, he died penniless.

Eadweard Muybridge — Muybridge was as strange as his invented name and certainly not a photojournalist in any classic sense. But his work in settling a bet on whether all four hooves of a horse leave the ground at a gallop make him a seminal documenter of scientific phenomena. Following him one could easily include the likes of electronic flash inventor Dr. Harold Edgerton, obsessive railroad photographer O. Winston Link and photographers of the mechanics of the natural world like Louie Psihoyos or James Balog.

Cameron portrait of Julia Prinsep Jackson, later Julia Stephen, Cameron’s niece, favorite subject, and mother of the author Virginia Woolf.

“The Red Man” photograph by Gertrude Käsebier

Julia Margaret Cameron and Gertrude Käsebier — History is filled with white men, even though women and other races are innovating alongside the counterparts that have generally held the pens and purse strings. These two women came to photography relatively late in life, and broke gender presumptions to make extraordinary portraits on two sides of the world — Cameron in Britain and Ceylon, and Käsebier in the U.S. Their styles were rich, intimate, personal and beautiful.

The iconic ruins in Canyon de Chelly, Ariz., by Timothy O’Sullivan.

Timothy O’Sullivan — This Civil War combat veteran, photographer of Gettysburg and one of Brady’s minions made his own distinct name by making some of the first best images of the American West. His romantic pictures of the mountains and canyons of the frontier arguably fueled western expansion by demystifying the region and romanticizing its beauty. On the other side of the planet a contemporary, John Thomson, was exploring China with a camera, for purposes of documenting the reality of that ancient culture for those back in Europe who could not go there. His images are not only beautiful, but filled with intricate detail and volumes of information. Would have National Geographic existed yet…

White Man Runs Him, a Crow scout serving with George Armstrong Custer’s 1876 expeditions against the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne that culminated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Edward S. Curtis, c. 1908.

Edward S. Curtis — Curtis, funded with $75,000 by J.P. Morgan in 1906, set out to photograph The North American Indian. Making beautiful portraits of disappearing cultures was the superficial goal, but ethnologists and historians discredit his work for its romanticism over accuracy. Curtis sought the beauty in the subject and amplified it by dressing his subjects in elaborate head dresses and clothing inappropriate to their cultural history. Despite the fictionalized images, the breathtaking collection he made still provides a document of peoples making a transition into the 20th century and humanizes formerly maligned and belittled peoples. His images have echoed not only down the line of documentary portrait photographers, but in the work of fashion greats Irving Penn and Richard Avedon who made loosely real portraits of visually compelling cultures decades later. Curtis had a little-known contemporary who did a much more ethical-in-our-eyes job of it: Frank (Sakae) Matsura, a Japanese photographer who set out to photograph Native Americans in their daily lives then, often dressed in European clothes and struggling to adapt to a foreign culture. Gertrude Käsebier at the same time applied her formidable portrait talents to photographing Native Americans.

Immigrant living in Victorian New York, by Jacob Riis.

Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine — Riis started a tradition, continued by Hine twenty years later, of using the camera as a tool to document social injustice and grab at the hearts and minds of readers. As a reporter who used the camera to prove his point, Riis crusaded against immigrant living conditions in New York’s slums. Hine saw the camera as his principal tool, however, and used it to fight against child labor. Riis’ flash powder illuminated dingy dwellings. Hine charmed, conned and cajoled his way into mines and factories to photograph the tiny children working there. The work of both helped change old laws or create new ones to protect underprivileged citizens. Their work has influenced all that followed, from the Photo League to the Farm Security Administration and the photographers of the Civil Rights Movement such as Danny Lyon and Bruce Davidson to any documentary photographer working for social change.

Child labor, by Lewis Hine.

Starry-eyed in the Digital Age

Posted by Kevin Moloney in Digital, History, Practice, Professionalism, Uncategorized on June 7, 2010

Stars from a moonless and little-polluted midnight sky shine over the distinctive buttes at Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park in southern Utah. © Kevin Moloney, 2009

There’s a spot I love to camp in Utah, on the edge of a red rock canyon miles from the nearest town. On a clear moonless night the stars are so rich that I can never sleep. I spend most of the night gazing at the curls and eddies of the Milky Way, smiling at passing satellites and listening to wind hiss off the wing feathers of diving swallows working the cliff-edge currents.

“I’ll find a deal on a clock drive,” I’d think to myself, wondering how I could photograph this amazing visual. I’d get the star-tracking device astronomers use to keep a far-off celestial object in their lens for longer than a few seconds.

Below a starry sky, light from the Glen Canyon Dam upriver glows from cliff faces on the Colorado River below the dam. © Kevin Moloney, 2010

Using film, or a digital camera only three years ago, it would have been necessary to expose for hours to get the detail I wanted. And without complex engineering the stars would all move and become the clichéd star trails in a camping photo. The clock drive would be a compromise too, as in relation the ground would move. Capturing both that sky and the canyons below it would be a daunting task.

Now camera manufacturers have reached astronomical heights in low-noise ISO, and making that photo is remarkably simple: A bright lens, ISO 1600 or so and maybe 30 seconds. In that time the stars don’t move much and the camera’s sensor seems to see into even the shadows of light cast through the atmosphere by a city a hundred miles off, or from the stars themselves. I just have to get back to that favorite spot under a new moon.

But it’s not just about stars and gimmicks. As the photographers of the last century must have felt when film reached ISO 100, “You can photograph anything now.”

ISO has become such a versatile and useful element in the equation of photography that I wish camera makers would promote the controls for it to the same level as shutter speed and aperture. I want to change it as often as I change those two.

For Harry- or Mary-DSLR-owner this means great cushion in getting that family moment onto Facebook. For a professional photojournalist, though, it is versatile power. Some of the world’s most disturbing, telling or satisfying moments happen after the sun is down, in only the smallest hints of light. What every storyteller wants are better tools with which to tell the full story.

This power was immediately put to use in the toughest places. Images of conflict and injustice in the night started appearing as fast as this generation of cameras appeared. Look, for example, at the work of Tyler Hicks and Michael Kamber. Also, while searching unsuccessfully for one image (possibly by Hicks or Kamber) I found the work of Michael Yon.

And in their latest edition, National Parks magazine filled their cover and several inside spreads with starry landscapes. The story was written by my colleague and sometime student Anne Minard.

Four-wheel-drive trucks pass the dune field of the Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve as the stars roll over on a moonlit night. With film like this, a beautiful, but different story. © Kevin Moloney, 2007

Another of the great gifts of digital photography is the perfect ability to correct color in white balance. This has been there since the first RAW files on my notoriously bad Nikon D1. (Give it a break. It was first out of the chute for truly usable digital cameras.) Film corrections took exposure-robbing filters that needed a huge investment in time and money to reach commercial perfection.

These wonderful tools are certainly helpful to amateurs too, and lately a few colleagues have admitted being nervous about them in the hands of just anyone. I suppose in days of old it was as much the technical craft of photography that separated us pros from the great un-hypo-cleared masses as anything. Only we had the know-how to correct fluorescent lights and expose at ISO 3200. But what has separated us from just anyone with a camera is the ability to tell the story well and accurately.

It’s not the tools that do the job. It’s the experience of the photographer that does.

This is a beautiful age in our art. Not only do we have almost all the power of the film world still at hand, but we have the ever expanding power of the digital world at our fingertips.

This is my ode to the digital age. Never has our toolbox been so full.

###

Thank you for being patient between posts as I teach, study and shoot. Summer is here!

Charles Moore (1931-2010) and the Background Noise of a Generation

Posted by Kevin Moloney in History, Practice, Uncategorized on March 17, 2010

Charles Moore: I Fight With My Camera

Charles Moore is the legendary Montgomery photojournalist whose coverage of the Civil Rights era produced some of the most famous shots in the world (the dogs and fire hoses in Birmingham, the Selma Bridge, and Martin Luther King’s arrest in Montgomery, among many others.) His photographs are credited with helping to quicken the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The noted historian, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. said that Moore’s photographs transformed the national mood and made the legislation not just necessary, but possible. This is his story.

Each semester, as I show some of the work of Bruce Davidson to my students, I find myself wondering why I can only name a few photographers who deeply covered the Civil Rights Movement: Davidson, the recently deceased Charles Moore, Danny Lyon, Gordon Parks… There are a few others.

The events of the movement — big and small, violent and not — are the material of photojournalism dreams. As we develop as photographers we imagine honing in on where the world is changing, going there and documenting history in the making. As a culture we look back with awe at what was accomplished by brave activists, marchers and average citizens.

But why does it seem so few photographers of the time honed in on that movement as a historic change in American history? Like today, there were tens of thousands of photojournalists in the U.S.

Perhaps it was the background news noise of a generation. We feel the brief flash of an earthquake, but not the constant continental drift. I’m sure many more photographers than those above were dispatched to a march, a riot, an arrest, and covered them as one-off news events without ever sinking into that time of great change as a story itself.

So what is happening today, around us, as background news noise, that will be an astounding piece of history to the next generation? And when will we start working on it?

Ode to the Underwood: In Praise of the Mechanics of Creativity

Posted by Kevin Moloney in Film, History, Practice, Uncategorized on March 17, 2010

As I sit and type this gently on the elegant and thin modern keyboard of my computer, I find myself wishing for the catharsis of a mechanical typewriter.

Behind me, on the other end of my office, is my grandfather’s 1923 Underwood upright. As a kid I pounded on it until all the keys bunched up in a wad. I rolled the platen. I rang the little end-of-line bell.

I love computers and digital technology. I am fascinated by the powerful communication tools offered by the 21st century. But nothing beats a cool mechanical device. The sensuality adds to the creative process.

Writing on that machine — a few high school papers when my father wouldn’t let me on his IBM Correcting Selectric — was a physical endeavor with all the rewards of exercise. You swing fingers into the long throw of the keys, controlling the strength of a word through how hard you pounded the letters. The emotion of a word or line exploded into the act of typing.

Each line musically ended with a sweet ding and a gratifying swipe at the carriage return lever. Through the process your mind needed to stay three steps ahead of your fingers, plotting each word and paragraph in advance to avoid a retype of at least a page. When that page was done, you could melodramatically grab the paper and yank it out of the platen with a satisfying and final buzz of the ratchet.

Just over a year ago I pulled out the small portable Smith-Corona my father used in college. I thought my seven-year-old guests would be happily occupied banging on the keys and tangling the font the way I did. “Is this an old computer?” Zoe asked with a gasp of fascination.

In photography I get the same pleasure from pulling a dark slide out from in front of a fat sheet of film, or from cranking a film roll into a Rolleiflex, or from cocking the shutter of an old Flash-Supermatic leaf shutter. I listen to the soft trip of a Leica M3 at 1/60 second and savor the polished roll of the advance lever mechanics. The sense of beginning in those actions is so much more palpable than in the slip of a memory card into a slot and the tinny ping of a DSLR.

In a darkroom I still relish the feel of a roll winding onto the stainless-steel reels, the sour smell of the hypo, the suds of the Photoflo. Watching an image appear as I tip the corner of an amber-lit tray takes me instantly back to age 15, a basement darkroom, and the excitement of discovery.

But I am not a Luddite. I am a master’s student in Digital Media Studies at the University of Denver as well as a working digital photojournalist and photojournalism teacher. I find sensuality in the visual and aural output of the digital age and the elegance of its engineering. But that’s another post.

My message is only this: Remember to embrace the process of your work and find joy in it the way you find it in your images. As le maitre Henri Cartier-Bresson excitedly giggled and growled:

“For me it’s a physical pleasure, photography. It doesn’t take many brains. It doesn’t take any brains. It takes sensitivity, a finger and two legs. But it is beautiful when you feel that your body is working or, like this, full of air… And in contact with nature… It’s beautiful!… Pow… Grrrettta… Arrruff! …You see?!”

W. Eugene Smith at the Jazz Loft: Hard Times and Multimedia

Posted by Kevin Moloney in History, Uncategorized on February 4, 2010

The Jazz Loft (Linked from The Jazz Loft Project)

I was out of the country teaching photojournalism in southeast Asia when this series aired on WNYC and in edited form on NPR nationally.

The series first crossed my radar as a jazz head and grabbed me as a W. Eugene Smith fan. Of particular interest to photojournalists is episode two, “Images of the Loft.”

Smith has long been one of my heroes for his polishing of the photographic essay form, starting with his 1948 Country Doctor essay and on to Minamata, one of the most powerful pieces of environmental journalism ever done.

Between the two he beautifully photographed Dr. Albert Schweitzer, nurse-midwife Maude Callen, a village in fascist Spain, Haitian insane asylums and many others.

Between that famous work for Life magazine and the stunning Minamata book, he lost himself, barely able to leave a dingy loft on New York’s Sixth Ave.

W. Eugene Smith at his loft window (linked from NPR.org)

He continued to photograph — a personal and introverted essay shot entirely through his fractured window, “As From My Window I Sometimes Watch,” and thousands of images of the jazz musicians, such as Thelonious Monk, who came and went through the tenement at all hours of the day and night.

He also printed and collected obsessively, and tried to edit and reexamine his massive, beautiful and improvisational body of work from Pittsburgh.

At the same time, new technologies appeared that appealed both to Smith’s documentary impulses and to his undying interest in music — the tape recorder.

Late last year, Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies and WNYC produced an extensive audio documentary and book on The Jazz Loft where Smith lived. The program’s dual focus on Smith and the jazz musicians who jammed there is only possible thanks to Smith’s recorder, thousands of tapes, and his obsessive nature.

An exhibition of images will open at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts on February 17 and run through May 22, 2010. It will travel to the Chicago Cultural Center, Duke University and the University of Arizona where Smith’s archive resides.

If Smith captures your imagination, admiration and sometimes train-wreck fascination the way he does with me, see the exhibition. Also seek out the 1989 docudrama “Photography Made Difficult,” and the 2003 book on his three-year, 11,000-frame Pittsburgh project.

When in 1888 George Eastman put the

When in 1888 George Eastman put the